Today, Ohioans wear the 鈥渂uckeye鈥� nickname with pride, but it is sort of unusual 鈥� when you think about it 鈥� that a tree with an odd nut is the namesake so universally honored and accepted in the state. We know that the buckeye tree was native to the land where Ohio now sits, but why exactly did its people come to be known as Buckeyes?

It turns out the often-repeated story of the first person ever to be called a buckeye might be a fabrication, according to one local historian.

The earliest instance of a person being called a buckeye was written by Samuel Prescott Hildreth in 1852.

In his telling, it took place during the ceremony opening the first court in Marrietta, Ohio in 1788. The local sheriff, Colonel Ebenezer Sproat, led the procession on horseback with a sword in one hand and a wand in the other. The story also includes the description of a group of friendly indigenous people looking on in amazement, shouting 鈥渉etuck鈥� 鈥� a word meaning 鈥渂ig eye of the buck鈥� 鈥� at the tall imposing figure.

Historian Raymond Irwin was curious about the widespread use of the buckeye nickname and when he started digging into the story, he didn鈥檛 find evidence to back it up. It seemed like Hildreth鈥檚 version of the origin story persisted largely because Hildreth was considered a trusted source.

鈥淚t was surprising how quickly the story that Hildreth tells takes hold, and it's repeated all the way up to the present day,鈥� Irwin said. 鈥淥hio State Athletics still uses it to promote the idea of being a Buckeye.鈥�

Irwin found several problems with the story. First, no other account of the ceremony mentions native people shouting 鈥渉etuck.鈥� Second, the word itself does not appear to be part of any native people鈥檚 language in reference to an 鈥渆ye,鈥� buck,鈥� or 鈥渄eer.鈥� Third, no other history of Ohio before 1852 includes the story and in fact, Hildreth鈥檚 own earlier work doesn鈥檛 mention the buckeye connection.

鈥淏etween 1848 and 1852, he describes the same scene, but in vastly different ways,鈥� Irwin said. 鈥淪o in 1848, he never mentions anything about indigenous onlookers yelling "hetuck" at Sproat, and then four years later... it's a massive change.鈥�

So if Hildreth did add a bogus detail about the buckeye nickname, why did he do it?

First, it is important to note that in the early 1800s, the term 鈥渂uckeye鈥� had a decidedly negative meaning.

鈥淭he buckeye tree was known to the white settlers of the region as being useless,鈥� Irwin said. 鈥淭he meaning of the word buckeye originally was fake or useless. So you could be called a buckeye lawyer or a buckeye doctor or a buckeye Christian, which just means false or fake.鈥�

By the 1820s however, buckeye started being used in a different way. Irwin found references to buckeye as a name for people who were born on the frontier. A Maryland newspaper reported a story in 1826 about a sharpshooting contest between four locals and four 鈥淏uck-Eyes.鈥� Also, an 1830 children鈥檚 novel contained a passage about the name of the buckeye tree and explained that backwoodsmen native to the western forests were called buckeyes.

Another sign of change was when historian Dr. Daniel Drake spoke at a celebration in Cincinnatti in 1833. With poetic language, he enthusiastically embraced the name buckeye for himself and his fellow Ohioans. Later, the nickname was used in the campaigns of William Henry Harrison and other Ohio politicians.

The name gained wider usage over these decades and since there was no clear definitive explanation, Hildreth may have invented the 鈥渉etuck鈥� story to rehabilitate any lingering negative connotations surrounding the word.

鈥淚 think it is a conscious attempt to give Ohioans a nickname that was worthy of the development of the state at the time,鈥� Irwin said.

Also, it鈥檚 just a good tall tale.

鈥淵ou can envision this massive man, six foot four and broad shoulders, and these mysterious characters in the background who are yelling at him and it involves the symbols of war and of state,鈥� Irwin said. 鈥淵ou can see why people pick it up because it's just a much better story than the transformation of the image of a tree.鈥�

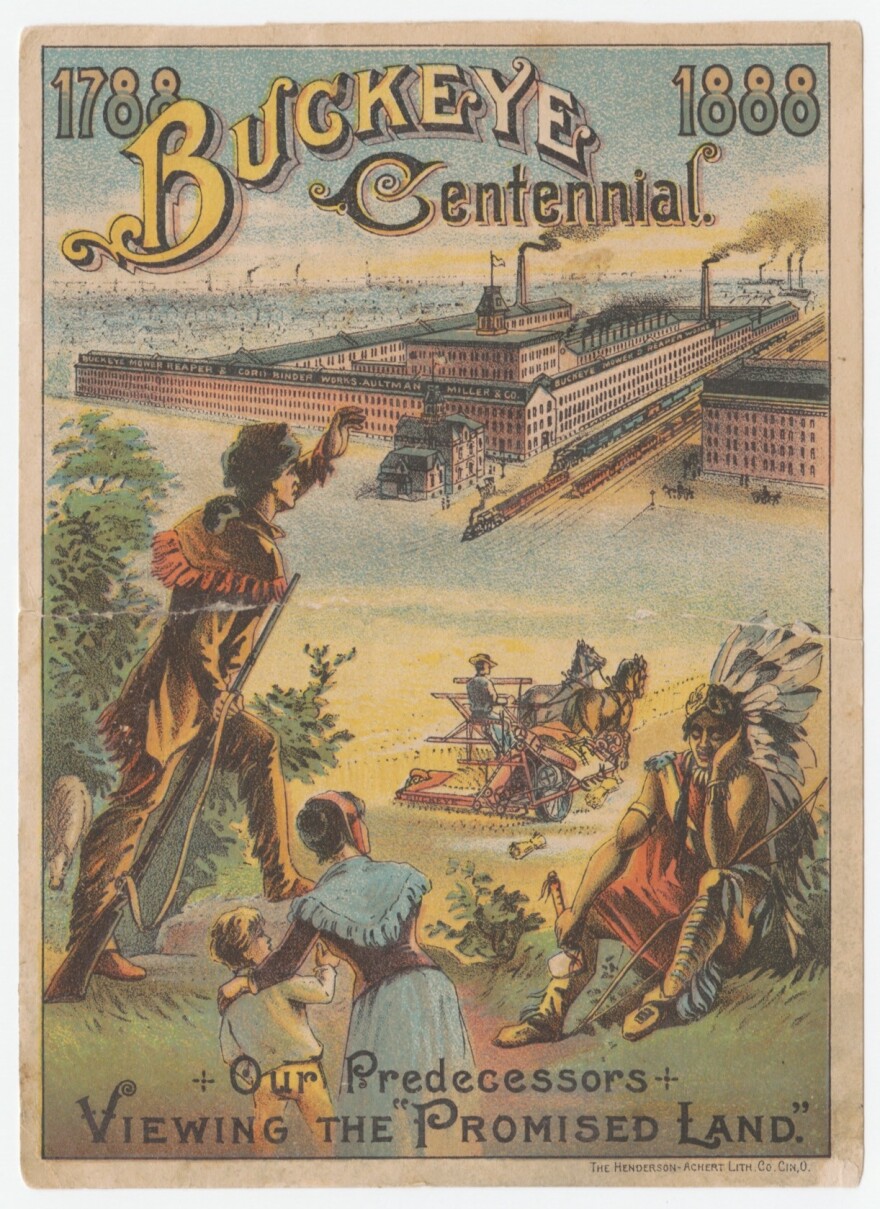

Irwin also believes the story perpetuates a false narrative about the relationship between white settlers and native people. Hildreth鈥檚 other descriptions of indigenous inhabitants are far less flattering and by 1852, the last native group living in Ohio 鈥� The Wyandot 鈥� had been forcibly removed.

鈥淚 think there is a pinch of guilt among the descendants of the first white settlers, and you can see this in the documentary record that they are just not happy with the way the removal happened,鈥� Irwin said.

A century later, the Ohio State University adopted the buckeye as its mascot and the state officially made the buckeye its state tree. With no real reason to question Hildreth鈥檚 account, the story spread and was repeated again and again in state histories, children鈥檚 books, and .

Irwin said he hopes his research will help correct the record and that the many businesses and institutions that honor the buckeye nickname will embrace its true origin.

鈥淚f we want to have a claim as Buckeyes who are interested in truth and we're interested in inclusiveness and in good policy, we probably should seek the truth whenever we can,鈥� Irwin said.

Irwin鈥檚 essay 鈥淭he Origins of the Buckeye Nickname鈥� is forthcoming in the Fall 2022 issue of the Ohio History journal.