This story originally ran on October 9, 2017, before Officer Zachary Rosen was rehired. The story has been updated.

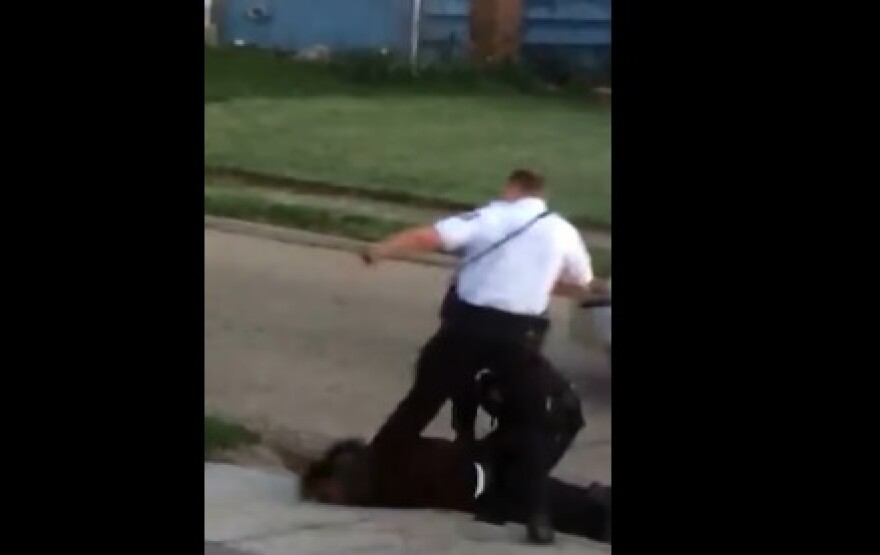

Zachary Rosen was fired from the Columbus Division of Police in July for kicking a handcuffed suspect in the head, an incident caught on video and which Mayor Andrew Ginther called вҖңunacceptable and inconsistent with our values as a community.вҖқ

The Fraternal Order of Police said the firing was a вҖңpolitical decision.вҖқ But when the news first broke, FOP Lodge No. 9 president Jason Pappas seemed confident Rosen would be rehired.

вҖңEveryone know heвҖҷs going to get his job back,вҖқ Pappas said.

More than half a year later, Pappas' prediction came true: Rosen was on March 5, thanks to arbitration with the FOP.

from the Washington Post found police departments around the country are regularly forced to reinstate fired officers after union arbitration. The nationвҖҷs largest departments fired at least 1,881 officers for вҖңmisconduct that betrayed the publicвҖҷs trust,вҖқ and rehired more than 450.

Police personnel records obtained by РЗҝХОЮПЮҙ«ГҪ show that, in the past decade, Columbus Police have fired 14 officers and rehired three of those officers after appeals from the FOP.

Cut From The Force

The reasons for firing, and details provided, vary: Richard Higaki failed to pass a firearms training assessment. Amber Spires вҖңabandoned her post.вҖқ Zachary Fisher was caught with child pornography, for which he was eventually prosecuted.

A few officers were fired for dishonesty. Shea Brintlinger was terminated for untruthfulness and insubordination. Michael Tucker lied that a suspect took and passed a polygraph test. Kevin Morgan missed 11 special duty shifts and arrived late to or left early from five others, receiving payments for shifts he did not work.

Some officers did not perform up to the Division's standards. Sarah Wheeler performed poorly during her probationary period. Jess Wheeler's personnel file says he lacked motivation and safety skills.

Other officers' firings were due to drug use. Matthew Freetage was terminated for untruthfulness during an investigation and accepting a coworker's pills while on duty and in uniform. James Hassey obtained and supplied marijuana to his sister and girlfriend.

When an officer in Columbus is fired, the Police Chief and the city Public Safety Director must sign off. In RosenвҖҷs case, Chief Kim Jacobs initially recommended a 3-day suspension, and Public Safety Director Ned Pettus chose to dismiss Rosen instead.

Ginther and Columbus City Council both said they agreed with the decision to fire Rosen. But that call isnвҖҷt necessarily set in stone.

Chances For Appeal

Once an officer has been fired, they have the right to appeal the decision and ask the union to arbitrate. In arbitration, the city and the FOP agree to use an independent and neutral party to decide dispute resolution cases.

вҖңArbitrators have come up with what they basically call the seven вҖҳjust causeвҖҷ determinations as to whether or not a case can be arbitrated. We rely on that list,вҖқ Pappas says. вҖңThatвҖҷs things like whether the employee has been forewarned of the consequences of his actions, (or) are the employerвҖҷs rules reasonably related to business efficiency.вҖқ

RosenвҖҷs case shows some similarities to another Columbus officer, Norman Baldwin. He was fired in 2015 for kicking a suspect in the face and not reporting it.

Though kicking a person in the head is not necessarily against department policy, Columbus Police called BaldwinвҖҷs kick an вҖңunreasonable use of force.вҖқ The same thing happened with Rosen, whose kicking of an unarmed, restrained suspect was found to be an вҖңuntrained technique.вҖқ

However, the FOP decided not to take up BaldwinвҖҷs case for an appeal.

вҖңIn NormвҖҷs case, it wasnвҖҷt the use of force that became the issue,вҖқ Pappas says. вҖңAs a result of the investigation, it appears that he was untruthful about the reporting of the use of force for a period of months, then ultimately at a ChiefвҖҷs hearing, admitted to such.вҖқ

Rosen, on the other hand, self-reported his actions, even before a of the incident caused an outcry. And four lower-ranking supervisors said his actions were within policy, before JacobsвҖҷ recommended disciplinary actions.

Two Came Back

After RosenвҖҷs firing, FOP immediately filed for arbitration and began the appeals process.

In Columbus, the majority of officers who are fired do not get rehired. Two officers, however, did win their jobs back.

The first was Chad Knode. Knode was fired two years ago in the wake of a scheme where another Columbus officer and a city employee made tens of thousands of dollars by scrapping old equipment meant for the city. That other officer, Steven Dean, was allowed to retire instead of being fired. He eventually went to prison.

Knode wasnвҖҷt directly involved in the scheme, but the city fired him because they said he should have known. He eventually won his job back because of an otherwise clean record. Arbitrators said Knode was also never warned about the consequences of not reporting such actions.

The other rehired officer was Eric Moore, who was originally fired in 2016 for overtime fraud. Police say he improperly sought payment for overtime 39 different times, claiming nearly $10,000.

Moore was rehired during arbitration because police say he was working from home at least part of that time.

Frustrations On Both Sides

A common argument among police unions is that chiefs are prone to overreach, especially when theyвҖҷre under political pressure. FOP Lodge 9 seems to share that view of disciplinary decisions.

вҖңI think firing people unjustly is way greater of a problem for morale than bringing someone back who was unjustly terminated,вҖқ Pappas says. вҖңWe either have due process and weвҖҷre going to follow it, or weвҖҷre not. And in those particular cases, I believe morale is significantly hampered.вҖқ

In August, FOP Lodge 9 a vote of вҖңno confidenceвҖқ in Ginther, Pettus and City Council president Zach Klein. Pappas said then that ColumbusвҖҷ leaders violated RosenвҖҷs due process rights to a fair hearing.

Columbus Police denied several requests for an interview. A statement from Deputy Chief Michael Woods emphasized that they take employee dismissals seriously.

вҖңAfter careful consideration and determination that the employee has committed a policy violation so serious that they are no longer a valuable member of the Columbus Division of Police, we have to do what is right,вҖқ Woods wrote. вҖңHowever as an agency governed by laws, we must comply with arbitratorвҖҷs rulings that reinstate officers. It can be frustrating because taking this step means that we have determined they should no longer be employees of the Columbus Division of Police.вҖқ

ColumbusвҖҷ rate for rehiring officers is lower than other big cities, according to the Washington PostвҖҷs . For example, in the past decade Detroit fired 37 officers and rehired 5; Milwuakee fired 57 and rehired 11; and Oklahoma City fired 15 and rehired 6.

As far as Pappas knows, Rosen is the only Columbus officer in the arbitration process for a disciplinary reason right now. He couldnвҖҷt comment further because the case is pending.

Rosen was fired almost three months ago. Arbitration typically takes six to eight months.

Correction: An earlier version of this story named an officer who voluntarily resigned in good standing. His file was incorrectly provided by the Columbus Division of Police.